Deep-dive into .NET Core primitives: inside a .dll file

Examining the foundations of an .NET Core application

When I started working with C# and .NET, clicking the “Start” button in Visual Studio was magical, but also dissatisfying. Dissatisfying – not because I want to write code in assembly – but because I didn’t know what “Start” did. So, I started to dig. In a previous post, I showed some of the important files used in a .NET Core application. In this post, I’m going to look even closer at one particular file, the .dll. If you’re new to .NET Core and want to peek under the hood, this is a good post for you. If you’re already a .NET developer but wonder what actually happens with your *.dll files, I’ll cover that, too.

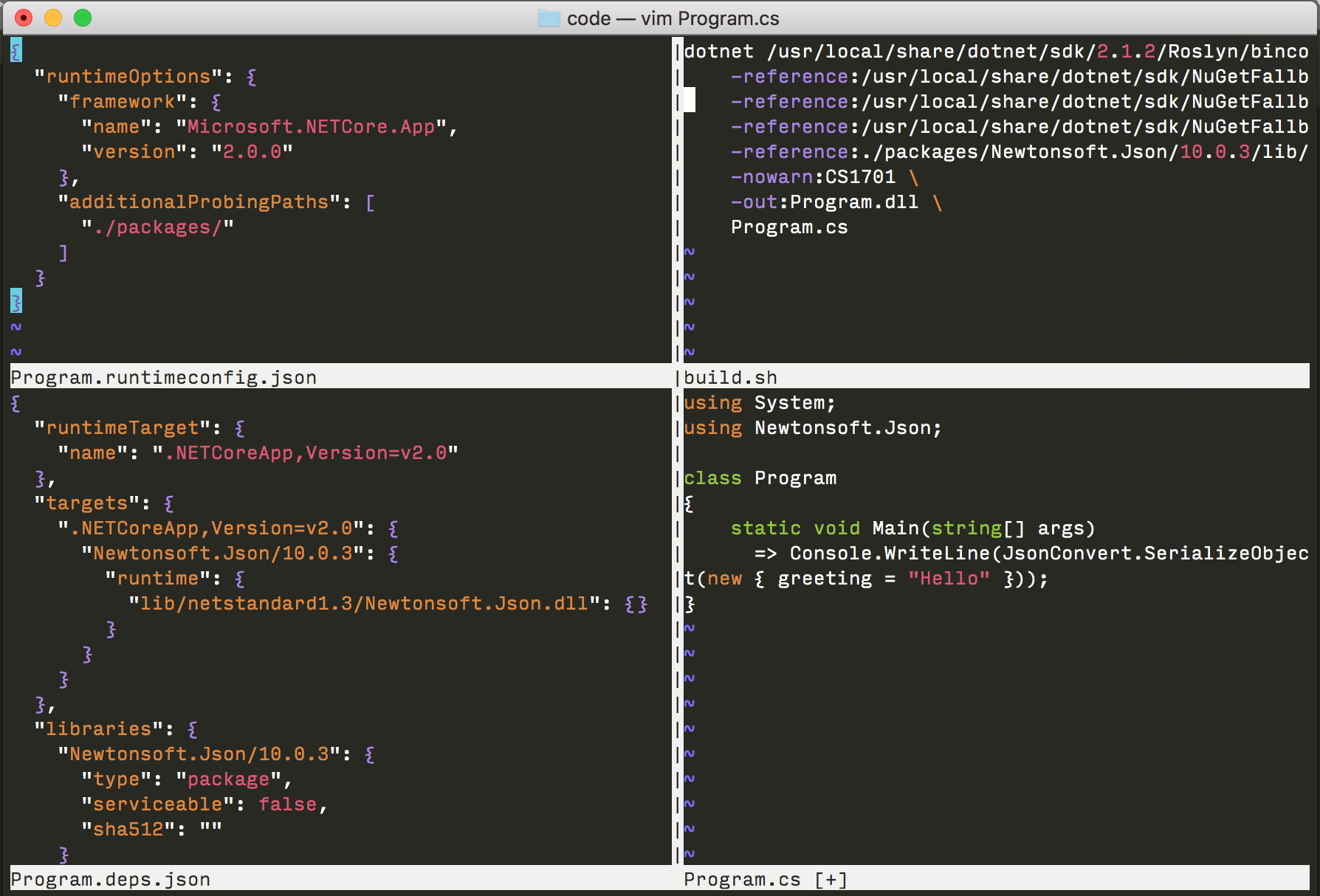

I’m going to abandon the magic of Visual Studio and stick to command-line tools. To play with this yourself,

you’ll need the .NET Core 2.1 SDK. These steps were written for macOS,

but they work on Linux and Windows, too, if you adjust file paths to C:\Program Files\dotnet\ and dotnet.exe.

You’ll also need to use the “ildasm” command, which is available in the Developer Command Prompt for VS 2017.

If you’re on macOS or Linux, dotnet-ildasm is a good-enough replacement.

See also Deep-dive into .NET Core primitives: deps.json, runtimeconfig.json, and dll’s.

ldstr “Hello World!”

C# must be compiled first before it can execute. The C# compiler (csc) turns .cs files into a .dll. A .dll file is a portable executable, and it primarily contains something called Common Intermediate Language, or IL.

In C#, a simple method looks like this, and is stored in a plain text file.

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Console.WriteLine("Hello World!");

}

The .dll contains the IL version, and is stored in a binary format.

By calling ildasm Sample.dll on command line, you can create a plain text representation of that binary format.

The matching IL looks like this:

.method private hidebysig static void Main(string[] args) cil managed

{

.entrypoint

.maxstack 8

IL_0000: nop

IL_0001: ldstr "Hello World!"

IL_0006: call void [System.Console]System.Console::WriteLine(string)

IL_000b: nop

IL_000c: ret

}

External API

Here is the complete IL

for a “Hello World” console app. It’s only 79 lines. If you skim through the IL, you may have noticed something:

the IL does not contain the definition for Console.WriteLine. Instead, the IL contains this near the top:

.assembly extern System.Console

{

.publickeytoken = (B0 3F 5F 7F 11 D5 0A 3A )

.ver 4:1:1:0

}

This is called a reference. My assembly, Sample.dll, references another assembly named System.Console. And to be more specific, it references System.Console, version 4.1.1.0, with a strong name public key token of B03F5F7F11D50A3A.

So where can I find System.Console? Trick question, sort of.

The compilation reference to System.Console.dll

As discussed in more detail in Part 1, the C# compiler is a console command which supports a flag

-reference. Visual Studio and the dotnet command line, through wizardry I won’t cover now, call the C# compiler

with arguments like this:

/usr/local/share/dotnet/dotnet /usr/local/share/dotnet/sdk/2.1.301/Roslyn/bincore/csc.dll \

-reference:/Users/nmcmaster/.nuget/packages/microsoft.netcore.app/2.1.0/ref/netcoreapp2.1/System.Console.dll \

-reference:/Users/nmcmaster/.nuget/packages/microsoft.netcore.app/2.1.0/ref/netcoreapp2.1/System.Runtime.dll \

-out:bin/Debug/netcoreapp2.1/Sample.dll \

Program.cs

The System.Console.dll in my NuGet cache is the compilation reference, which defines the System.Console assembly. The C# compiler read this file, which is how it determined that:

- the System.Console assembly is version 4.1.1.0 and has a public key token B03F5F7F11D50A3A

- this assembly defines a type named ‘Console’ in the ‘System’ namespace

- this type has a static method named ‘WriteLine’ which accepts one string argument

Now, if we ildasm this System.Console.dll file, we’ll see something interesting. The IL for this method

looks like this:

.method public hidebysig static void WriteLine(string 'value') cil managed

{

// Code size 1 (0x1)

.maxstack 8

IL_0000: ret

}

Let me translate this back to C#.

namespace System

{

public class Console

{

public static void WriteLine(string value)

{

return;

}

}

}

…hold up…how can that possibly work?

This method is empty because the .NET Core SDK is taking advantage of an important feature of .NET: dynamic linking,

also called assembly binding. .NET Core needs to run on Windows, Linux, macOS and more.

Rather than produce a single System.Console.dll file which has to work on every possible operating system and CPU

(some which may not even exist yet), the .NET Core team creates multiple variants of System.Console.dll.

The one the compiler read is called the reference assembly, and its purpose is to provide the C# compiler

with the available API, but not the implementation. Think of it like a C++ header file. This assembly

has intentionally been stripped of implementation, so all methods do nothing or return null.

The runtime reference for System.Console

When you execute a .NET Core app, a different System.Console.dll file is used. You can find its location by running an app with this:

Console.WriteLine(typeof(Console).Assembly.Location);

On my computer, this file was here:

/usr/local/share/dotnet/shared/Microsoft.NETCore.App/2.1.1/System.Console.dll

This file is the runtime reference, aka the implementation assembly.

How did .NET Core find this file? It used some heuristics based on the deps.json file and runtimeconfig.json files that sit next to my Sample.dll file.

Now, if we ildasm the implementation version of System.Console.dll file, we’ll see that it’s actually doing

something:

.method public hidebysig static void WriteLine(string 'value') cil managed noinlining

{

.maxstack 8

IL_0000: call class [System.Runtime.Extensions]System.IO.TextWriter System.Console::get_Out()

IL_0005: ldarg.0

IL_0006: callvirt instance void [System.Runtime.Extensions]System.IO.TextWriter::WriteLine(string)

IL_000b: ret

}

Closing

Assemblies are an essential primitive to understand to know how .NET Core really works. Most developers don’t really need to know all the details of IL and .dlls, but it’s good to have a general understanding of why they exist and what they do. This is only the tip of the iceberg. There are many, many more things involved in making a .dll execute in a .NET Core app, and lots of things I would love to explain. What happens if the compilation and runtime references are different? What’s a strong name? What’s crossgen? Can I obfuscate IL? etc. But I’ll leave those for another post, maybe.

More info

- The evolution of design-time assemblies. A fascinating read on some techniques the .NET team has used over the years.

- ILSpy - my favorite IL decompiler

- How .NET Framework locates assemblies - if you’re interested in comparing this to .NET Core

- .NET Framework: Redirecting Assembly Versions - in .NET Framework, assembly binding is much stricter about assembly versions and public key tokens that .NET Core…thanks goodness too. Hopefully, I never have to explain this error again: “The located assembly’s manifest definition does not match the assembly reference.”